Engineering Smart Therapeutics: Innovative Uterine Fibroid Treatment

By Ben Miller, MFA, PMP, Duke Clinical and Translational Science Institute

A collaboration by researchers at Duke and North Carolina Central University (NCCU) aims to offer a more convenient, less invasive treatment for uterine fibroids, one of the most common and under-studied issues in women’s health.

Uterine fibroids — benign tumors made of stiff collagen tissue that grow on the uterus — are common reproductive-age tumors. Sometimes these growths are harmless and can even go undetected, but in many cases they cause symptoms ranging from pain and bleeding to infertility. More than 80% of Black women and nearly 70% of white women have fibroids by age 50. Current interventions are either expensive, difficult to access or have significant systemic side effects.

After nearly a decade of working in parallel at campuses separated by just four miles, Friederike Jayes, DVM, PhD (above left), in the Duke Division of Reproductive Sciences, and Darlene Taylor, PhD (above right), professor of chemistry and biochemistry at NCCU, are now combining their research to advance a fundamentally new approach for treating uterine fibroids.

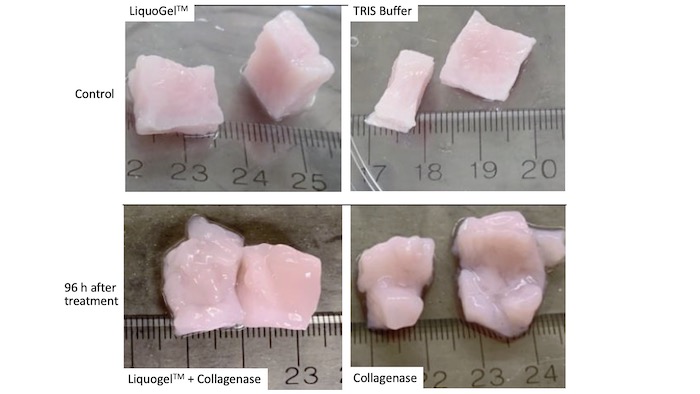

Dr. Jayes has long been fascinated with this problem and is involved in developing a new therapeutic treatment using a drug capable of breaking fibroids down inside the body. Since the tumors are collagen-based, the key ingredient in this intervention is collagenase, an enzyme that digests collagen. Meanwhile, Dr. Taylor has created a product called LiquoGel™, which serves as a platform to deliver drugs to targeted locations inside the body. Having known one another since 2008, they had long imagined combining the two lines of inquiry to fill what Dr. Jayes calls “the unmet need” of uterine fibroids.

“It was wishful thinking,” Dr. Taylor said. Dr. Jayes added, “We didn’t have the means to put them together.”

That changed in 2019, when they got their chance in the form of a pilot project grant from the Duke Clinical and Translational Science Institute (CTSI) designed specifically to facilitate the Duke-NCCU collaboration. The grant provided both funding and project management support.

“That funding award allowed us to combine the drug with LiquoGel™ for the first time and do a study,” Dr. Taylor said. “The project management piece was phenomenal as well. I don’t know that we would be where we are right now without that kind of support.”

LiquoGel™, when combined with a collagenase drug inside of a syringe, can be delivered directly to a tumor. It changes from a liquid to a gel inside of the body.

To understand how this combination works in practice, Dr. Taylor suggests imagining a bowl of gelatin with chunks of fruit suspended in it. In this analogy, LiquoGel™ is the gelatin, and the fruit is the fibroid-digesting drug. But there is one key difference: unlike a gelatin that someone would eat, which solidifies as it cools, LiquoGel™ firms up when it is warmed.

“The beauty of LiquoGel™,” Dr. Taylor explained, “is that it’s liquid at room temperature, and it becomes a gel at body temperature. Because of that, it gets delivered to the fibroid and becomes a gel. The co-dissolved drug is trapped during the gel process, and it’s much less likely that the drug will be washed out.”

In other words, the drug can be injected directly into the desired area and will stay there, doing its work without affecting other parts of the body. Over time, the LiquoGel™ partially degrades, allowing the body to get rid of it. Drs. Jayes and Taylor feel that uterine fibroids, because they are almost never fatal and only affect women, have not received the scientific attention they deserve.

Several other treatment options do exist, each with advantages and drawbacks. The ultimate resolution to uterine fibroids is a hysterectomy — major surgery to remove the uterus. While this solves the problem permanently, it also entails a lengthy recovery and means the patient could never again become pregnant.

“For some women, a hysterectomy is not desirable,” said Dr. Jayes. “It’s not a small thing. It is major surgery with risks.”

There are also less invasive surgeries to remove the fibroids, but this does not prevent regrowth and still involves pain and recovery. Certain medications can help, including birth control and other hormonal treatments, but these also have systemic effects on the body.

The combination of LiquoGel™ and the collagenase drug, by contrast, could be administered in a doctor’s office and would act only on the tumor itself.

While the Duke-NCCU award “stabilized the collaboration,” according to Dr. Jayes, much work remains before the treatment can reach patients.

The team has secured follow-on funding from North Carolina Biotechnology Center to conduct scale-up production of LiquoGel™ and time-course studies, as well as other essential research to facilitate the process of enabling clinical trials and ultimately seeking FDA authorization. At the same time, they intend to look at the social side of the uterine fibroid problem: what perceptions, beliefs and cultural issues inform the care that women receive and the care they want?

“We need to know if people would adopt the LiquoGel™ intervention,” said Dr. Jayes. “Where is this most needed, and what is the most desirable characteristic of it? We want our work to enrich the fibroid field.”