I think the most exciting thing about this study is that it creates a blueprint for researchers in other culturally and linguistically distinct settings to develop and test new illustrations to assess symptoms that are generally difficult to put into words — and may even prove useful in the U.S.

Q: What was your experience working in global health on your educational trip to Africa during a global pandemic?

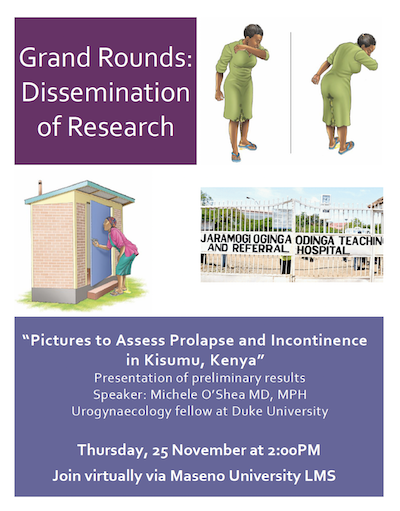

A. I worked with the Maseno University College of Medicine and the Department of Ob/Gyn at Jaramogi Oginga Odinga Teaching and Referral Hospital (JOOTRH) since 2019 to create a set of illustrations to assess for symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse (POP) and urinary incontinence (UI). We don't know the burden of pelvic floor disorders in many parts of the world — and in particular in sub-Saharan Africa, where the clinical and research focus has historically been placed on obstetric fistula. At the same time, most of our present written questionnaires assessing for symptoms were developed in a predominantly white, high school to college-educated population, and may not be appropriate even if they are translated into other languages like Kiswahili and Dholuo. Therefore, there is no good way of easily ascertaining patient symptoms of prolapse and incontinence among Kenyan women.

During a Grand Rounds presentation, I reviewed the basics of POP and UI with a group of medical students, as well as ob/gyn residents and faculty (115 people attended virtually), and then disseminated a research project we had been working on over the past 1.5 years with our gynecology collaborators. Our collaborators were Dr. Stephen Gwer and Dr. Jackton Omoto at Maseno University in Kisumu. In summary, the research project was focused on creating and validating a new set of illustrations — this was exciting because it's the first time illustrations have been attempted to help to assess pelvic floor symptoms and is particularly relevant in settings where there is not a high a literacy rate, or the dominant language is not primarily written.

Q. How did COVID-19 impact your work?

A. Of course, the pandemic thwarted my plans to initially go to Kenya in 2020, so we pivoted and performed virtual interviews via Zoom with gynecology nurses, residents and attendings to get feedback on these illustrations of prolapse, stress incontinence and urgency urinary incontinence, as well as facial representations of how each of these conditions. Then, after revising the illustrations based on this feedback, we pre-tested them with cognitive interviews among women presenting for outpatient care at JOOTRH earlier in 2021. They actually performed quite well, and no significant changes were required.

Finally, once travel restrictions were eased and the COVID-19 rates in Kenya were also coming down, I went to Kisumu, Kenya, to perform a validation study of these illustrations (basically comparing how well they did against the gold standard of a history and exam) among patients presenting for care at JOOTRH as well as two sub-county hospitals. I think the most exciting thing about this study is that it creates a blueprint for researchers in other culturally and linguistically distinct settings to develop and test new illustrations to assess symptoms that are generally difficult to put into words — and may even prove useful in the U.S.